“I was stunned”: The inside story of how Sharon Tucker won the caucus for Fort Wayne mayor

A deep dive into how she beat the establishment and made history

“It was a monumental day.”

That’s how one precinct chair summed up what happened Saturday at the Lincoln Financial Event Center at Parkview Field.

On just the second caucus ballot, the Allen County Democratic Party selected Fort Wayne City Councilwoman Sharon Tucker to succeed the late Tom Henry as mayor. She’ll be sworn in on Tuesday at 11:30 AM at the Clyde Theater, officially becoming the first Black female mayor in Fort Wayne history.

Before announcing that result to the crowd, Democratic Party chair Derek Camp gathered all seven candidates behind a blue step-and-repeat backdrop that separated the caucus-goers from the voting area.

He quietly shared with them that Tucker would be the next mayor. Several congratulated her with a hug, including Indiana State Representative and House Minority Leader Phil GiaQuinta, whom many saw as the favorite in the race.

Camp gave the group a few minutes to gather themselves. Tucker was understandably emotional, but so were the others.

It had been a long, grueling 54 days since Henry announced he had late-stage stomach cancer. Just over a month later, he died suddenly, and as required by Indiana state law, an April 20 caucus was called to replace him.

That meant his successor would be decided by the vote of the 98 Allen County Democratic Party precinct chairs who represented areas within Fort Wayne city limits.

With seven candidates in the running, it could have taken as many as six rounds of voting to meet the 50% plus one vote threshold to win. That’s why some in the crowd were surprised when Camp stepped to the mic to announce a victor after just the second ballot.

All seven candidates fanned out behind him, with Tucker on the far end of the group, almost out of view. Local news stations WANE and WPTA, having been tipped off about a winner, cut into their programming to carry Camp’s announcement live.

As he spoke, Tucker looked out at the crowd, then down at the floor. The mayor-elect took a deep breath, knowing that Camp’s announcement was about to change her life forever.

Forty-two hours earlier, Tucker had been alongside those same six people, and again in the same position: on the far end.

In the seating lottery for last Thursday’s town hall forum, she’d drawn the spot on the edge of the dais, as far as one could get from moderator Andy Downs without falling off the stage. That put her nearly — but not quite — out of the spotlights that were shining on all the other candidates.

More than 70 precinct chairs sat in the first few rows of the audience that night, many taking notes as they listened intently. By that point, they had also been hearing directly from the candidates — and their surrogates — for nearly three weeks.

“Everybody had been getting emailed, everyone had been getting called,” said Sean Johnson, a member of Tucker’s team who himself had been doing some of that calling. “They were being bombarded. All day, every day.”

That’s why, according to Johnson, Tucker decided the town hall would be her final act of persuasion, save for the five-minute speech she and the other candidates would give just prior to the first round of caucus voting.

In front of a crowd of several hundred at Purdue Fort Wayne that night, Tucker calmly navigated the questions posed to the panel, her grasp of city issues on full display. It helped that she has served on City Council since 2019 and prior to that spent four years as the only Democrat on the Allen County Council.

As I reported late Friday, she knew there were questions about her ability to raise enough money to secure re-election in 2027 were she to win the upcoming caucus, so she made sure to mention her recent fundraising success for Vincent Village, a transitional shelter for homeless families with children where she serves as executive director.

“In [the past] five months, I was able to raise $5.4 million,” she noted.

Afterwards, Tucker and her team felt confident in her performance at the town hall, according to Johnson, and decided to step back and give the precinct chairs space to make their decision.

Their work was pretty much done.

GiaQuinta, on the other hand — whom many saw as the candidate to beat in the race — wasn’t ready to stop campaigning quite yet.

He and his team weren’t going to leave anything up to chance. Things had really kicked into gear the previous Sunday evening, when they held a private event for every precinct chair — save the five he was running against — at Bergstaff Place in Fort Wayne. (I reported on it in this newsletter the next morning.)

The mood that night was jovial, according to several attendees. Local restauranteur Frank Casagrande and prominent Black businessman John Dortch both took the mic and voiced their support for GiaQuinta, as did recently retired Wayne Township Assessor Bev Zuber.

The GiaQuinta team appeared confident of victory. “We’ve got the votes,” one was overheard boasting that night. “We’re four votes shy of winning it on the first ballot.”

GiaQuinta had strong advocates in his brother Mark GiaQuinta and Tim Pape, both former Fort Wayne City Councilmen, but some precinct chairs who otherwise liked the two thought they might have actually hurt Phil’s cause this time around.

“I found them absolutely obnoxious during the campaign,” one told me.

As the precinct chairs would soon discover, GiaQuinta had a full-court press planned for the week leading up to the caucus. Endorsement letters from former Fort Wayne mayor Graham Richard, Dortch, Hoosier Heartland Area Labor Federation political director Mindy Rogers, and the Indiana AFL-CIO and Building Trades Union would appear in their mailboxes over the coming days.

One precinct chair told me they received a total of seven pieces of mail from GiaQuinta by the time the caucus arrived, by far the most of any candidate.

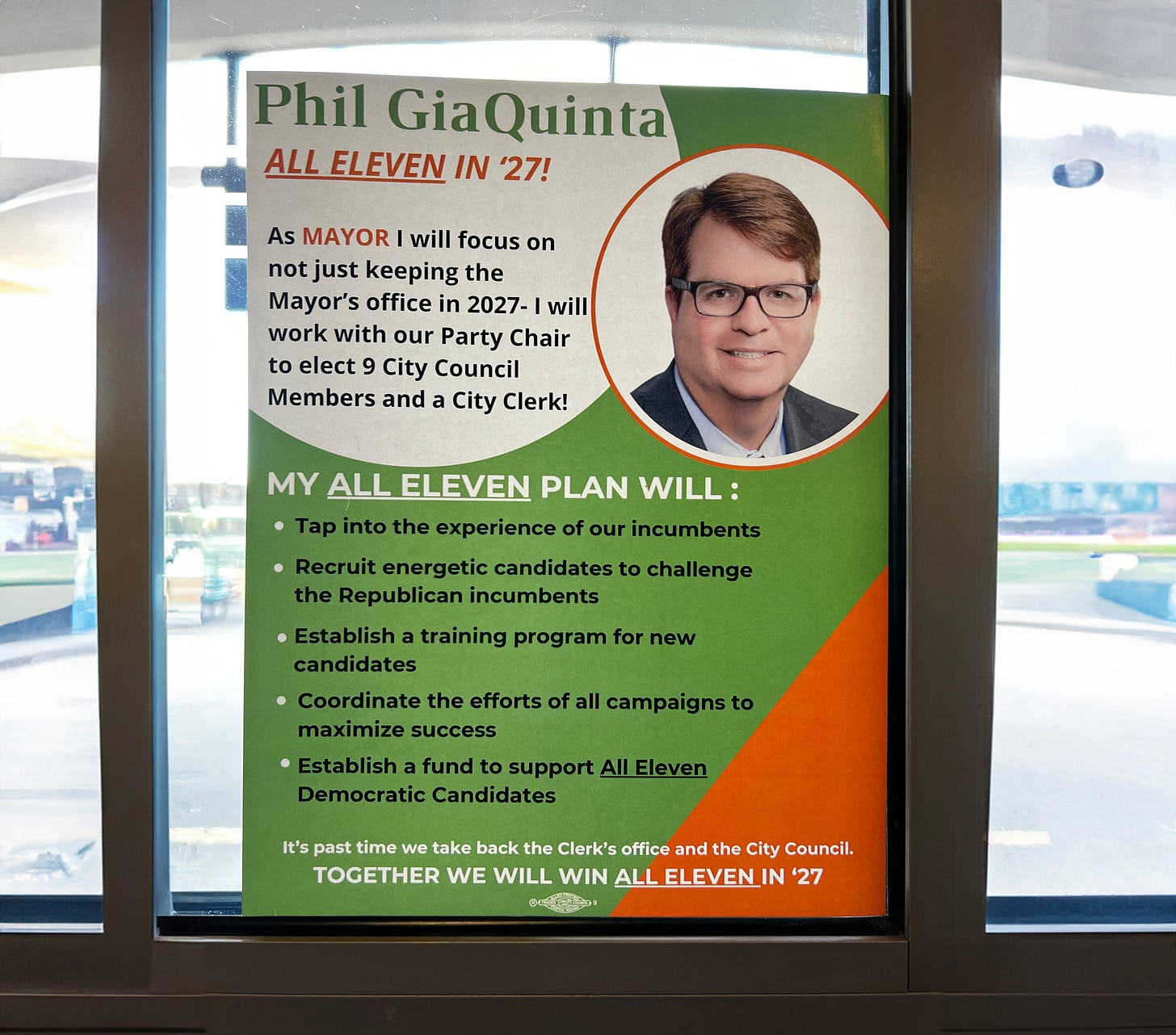

GiaQuinta also unveiled an “All 11 in 2027” plan he said would help the Democratic Party win all eleven city offices up in 2027: mayor, city clerk, and the nine members of city council. (Democrats currently hold only four of those eleven seats.)

It was designed to emphasize GiaQuinta’s electability and his capacity to fundraise, which many saw as his two biggest strengths relative to the other caucus candidates.

His team was running a classic political playbook, with a steady drumbeat of messaging and voter contact aimed to position GiaQuinta as the strongest candidate and safest choice in the race.

Ironically, that may have been part of their downfall.

“It felt like a [traditional] campaign,” said one precinct chair. “I don’t know that that’s what [we] were looking for.”

Tucker’s team did their fair share of campaigning, too, but that same precinct chair said those efforts felt more personal. Tucker sent out just two pieces of mail: a branded postcard and a letter of support from Adams Township Trustee Denita Washington.

The primary focus was on direct outreach to precinct chairs, both from Tucker and her surrogates. “It was about relationships,” said the chair, who ended up voting for Tucker.

Of course, GiaQuinta was also reaching out to each precinct chair directly, making calls and even knocking on their door when possible.

But when you combine his private event on Sunday, his steady barrage of endorsement letters, and the catered breakfast his campaign provided to all the precinct chairs the morning of the caucus, Team GiaQuinta was sending a strong signal: he was the best-funded, establishment-endorsed candidate in the race.

“Something I’ve learned about Democrats is they don’t like to be told who ‘the guy’ is,” said that same precinct chair who voted for Tucker. “[They] don’t like inevitability.”

Tucker also had another significant advantage over GiaQuinta: the fact that she was a black woman.

Other than Cosette Simon, who was appointed as acting mayor for eleven days when Mayor Win Moses was forced to temporarily resign due to campaign finance violations in 1983, every mayor of Fort Wayne up to this point has been a white man.

Numerous precinct chairs I spoke with felt it was time to change that.

As I reported last Friday, when the Allen County Democratic Party brought in two recently-elected Black female mayors — Deb Whitfield of Lawrence and Stephanie Terry of Evansville — to headline their annual fundraising dinner in March, many of them were galvanized to make the same thing happen in Fort Wayne in 2027.

In their minds, Henry’s tragic cancer diagnosis and sudden death gave them an opportunity to accelerate that timeline.

GiaQuinta knew that being the only white man in the race was a significant hurdle, and he tried his best to overcome it. In an answer to one of the first three questions at the town hall — all of which had been given to the candidates in advance — he said he would work hard to be a champion of diversity and progress as mayor.

“In my first thirty days [in office] I am going to do a diversity audit. I want to take a look at our boards and commissions and our city leadership,” he told the crowd. “I want to make sure that the city is represented by women [and] minorities like it should be. It should be reflective of the city of Fort Wayne.”

It wasn’t until after the town hall, however, that GiaQuinta and his camp discovered just how much his race and gender might close off a path to victory.

That’s when I published an article about Women United For Progress Allen County, which goes by the acronym WUFPAC. A nearly four-year old private Facebook group with 4,500 members, its stated mission is to get women, people of color, and members of the LGBTQ+ community elected to public office in Fort Wayne and the surrounding areas.

One longtime Democrat I spoke with suspected there might be as many as 25 WUFPAC members who were also precinct chairs. Early Wednesday, once I had obtained the complete list from multiple sources, I was able to confirm the actual number was much higher: 37.

Seeing that figure sent shockwaves through the GiaQuinta camp, I was told.

They knew that if none of those WUFPAC precinct chairs were planning to vote for him, he would need the support of 49 of the 59 others — more than 80% — in order to win.

“I don’t think [the GiaQuinta team] understood how strong the WUFPAC was [until that moment],” a precinct chair told me after the caucus was decided.

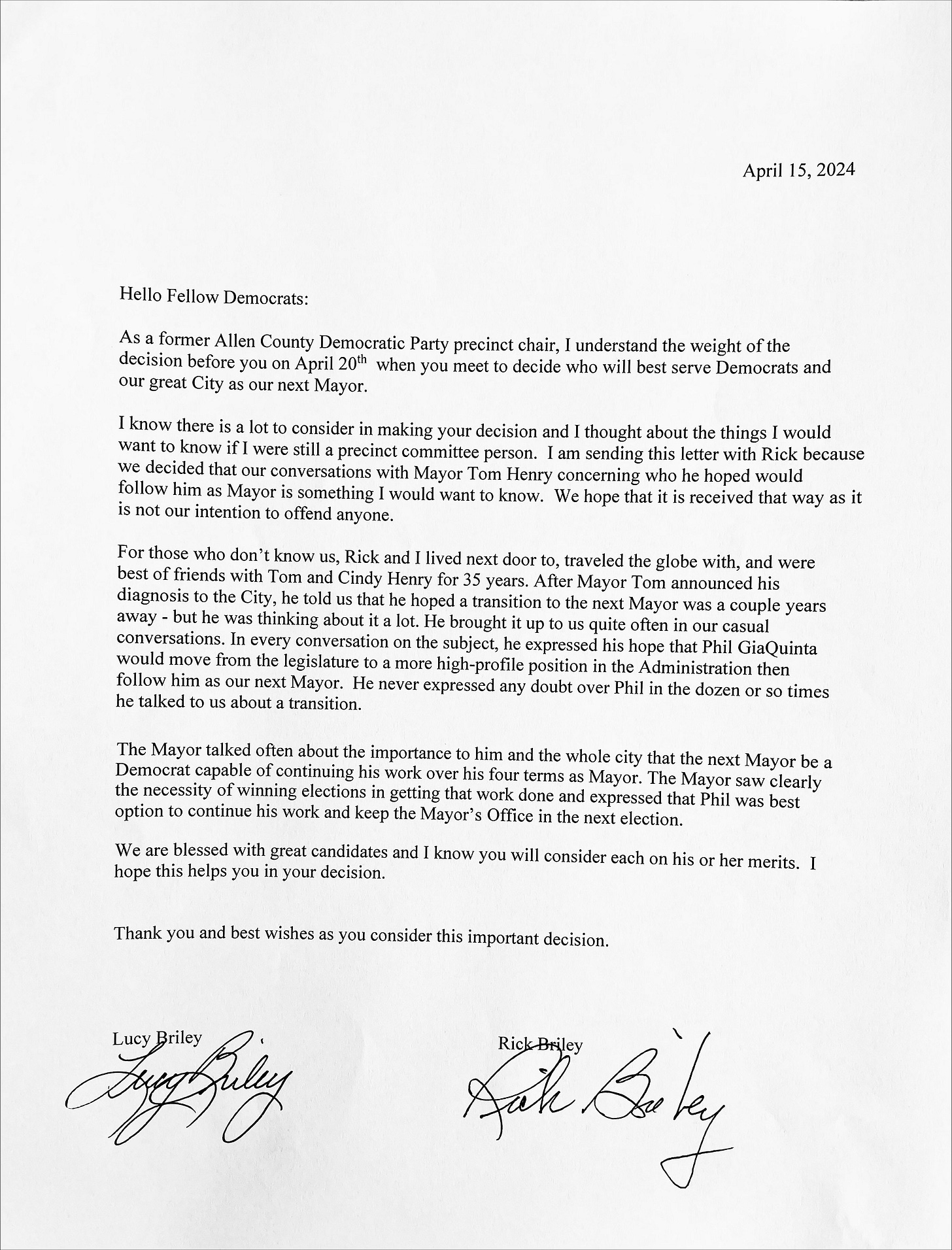

Still, GiaQuinta thought he might have an ace up his sleeve. On Friday, he emailed the precinct chairs a letter that had also been snail-mailed to them several days earlier.

“[The mail has] been slow this week, probably because of tax season!” he wrote in the email body, explaining that he was sending them each a digital copy to ensure they saw it before Saturday morning.

The letter was from Lucy and Rick Briley. Lucy is a former Democratic Party precinct chair and in it, she writes that she and her husband were next door neighbors and best friends with Tom and Cindy Henry for 35 years.

According to Briley, they spoke with Henry “quite often” about who he wanted to succeed him and in every conversation he said he hoped GiaQuinta would “follow him as our next Mayor.”

She says Henry’s stated plan was to have GiaQuinta join his administration in a “high-profile position” and then follow Henry as mayor, presumably after Henry’s resignation or death.

“I hope this helps your decision,” Briley writes as she closes the letter.

Based on my conversations with precinct chairs, this was the first time GiaQuinta had explicitly stated what had been whispered in Democratic Party circles since Henry’s death: that the late mayor preferred GiaQuinta follow him in office.

GiaQuinta had carefully avoided saying that in his calls with precinct chairs up to that point, but the letter marked a turning point where he was now explicitly claiming Henry’s endorsement.

GiaQuinta’s closing message seemed clear: I hope you’ll vote for me because that’s what Tom Henry wanted.

When Saturday morning finally arrived, the Tucker camp felt very good about her chances heading into the caucus.

As I reported on Friday night, the sense among party insiders was that she was the candidate with the momentum. One of her team members said they thought she had 34 votes locked up going into the first ballot.

The mood inside Team GiaQuinta was a bit less optimistic. It probably didn’t help that the crowd at their precinct chair breakfast was mostly older and white, according to one attendee. Even more notable, less than half the precinct chairs showed up.

At 10:30 AM, party chair Derek Camp gaveled the caucus to order. Vice chair Sheila Curry Campbell announced that 92 precinct chairs were present. That meant it would take 47 votes to win the caucus: 50% of 92, plus one vote.

As hard as it might be to believe, there were still some precinct chairs who hadn’t yet made a final decision. They wanted to hear each candidate give their final speeches just prior to the first round of voting.

“Sitting in that chair, before I had to go mark that first ballot, I could have gone either way [between Tucker and GiaQuinta] at that point,” one told me.

The seven candidates addressed the audience in alphabetical order: City Councilwoman Michelle Chambers, Fort Wayne director of intergovernmental affairs Stephanie Crandall, perpetual candidate Jorge Fernandez, citywide community liaison Palermo Galindo, GiaQuinta, Wayne Township Trustee Austin Knox, and finally Tucker.

When it was his turn, GiaQuinta strode to the podium. He had his speech printed out and spent most of his time looking down at his notes.

It soon became clear this wasn’t the rousing address he needed to pull out a win. “He read it like a book instead of reading it like a speech,” that same undecided precinct chair said.

A veteran political observer who was watching texted me: “Phil sounds like the fight has gone out of him.”

Tucker, on the other hand, gave her speech without notes — the only candidate to do so — and maintained eye contact with the precinct chairs throughout. She laid out the case for her candidacy and seemed to command the room in the process.

The precinct chair who had been waffling between Tucker and GiaQuinta said the difference in their speeches ended up being the deciding factor: they were voting for Tucker.

Another precinct chair said they didn’t think any of the other candidates were “as poised or put together as Sharon was.”

Tucker walked back to her seat to a round of applause and Camp returned to podium to walk everyone through the caucus voting process.

Finally, after three frenetic weeks of campaigning, it was time to start casting ballots.

It took about ten minutes to complete the first round of voting. Twenty minutes later, Camp stepped to the podium to announce the results.

It was unlikely that any candidate would have enough votes to win on that first ballot, but most expected GiaQuinta to be in the lead.

That’s why the first round results were so surprising. Tucker was in the top spot with 38 votes.

“I was stunned,” said one precinct chair. “I knew then it was over.”

GiaQuinta came in second with 30, followed by Crandall (10), Knox (9), Chambers (3), and Fernandez (1). Galindo — the only candidate who was not a precinct chair — did not receive any votes.

Fernandez and Galindo were cut from the next round due to caucus rules on lowest vote-getters. Knox and Chambers also announced they were dropping out.

Together, those candidates had gotten 13 votes that were now up for grabs.

Tucker only needed to secure nine of them to meet the 47-vote threshold for victory. GiaQuinta had to garner all 13, plus pull four more from Tucker or Crandall supporters to win.

As the second round of voting began, most people in the room could see the writing on the wall.

That included one precinct chair who told me they switched their vote from GiaQuinta to Tucker after hearing the first round results.

“I was a hard commit to Phil,” they said, “but you also have to realize what the people want, and what the people clearly wanted was Sharon.”

The woman the people wanted was standing alongside the other candidates in her familiar spot — on the end — as they waited for Camp to announce her win.

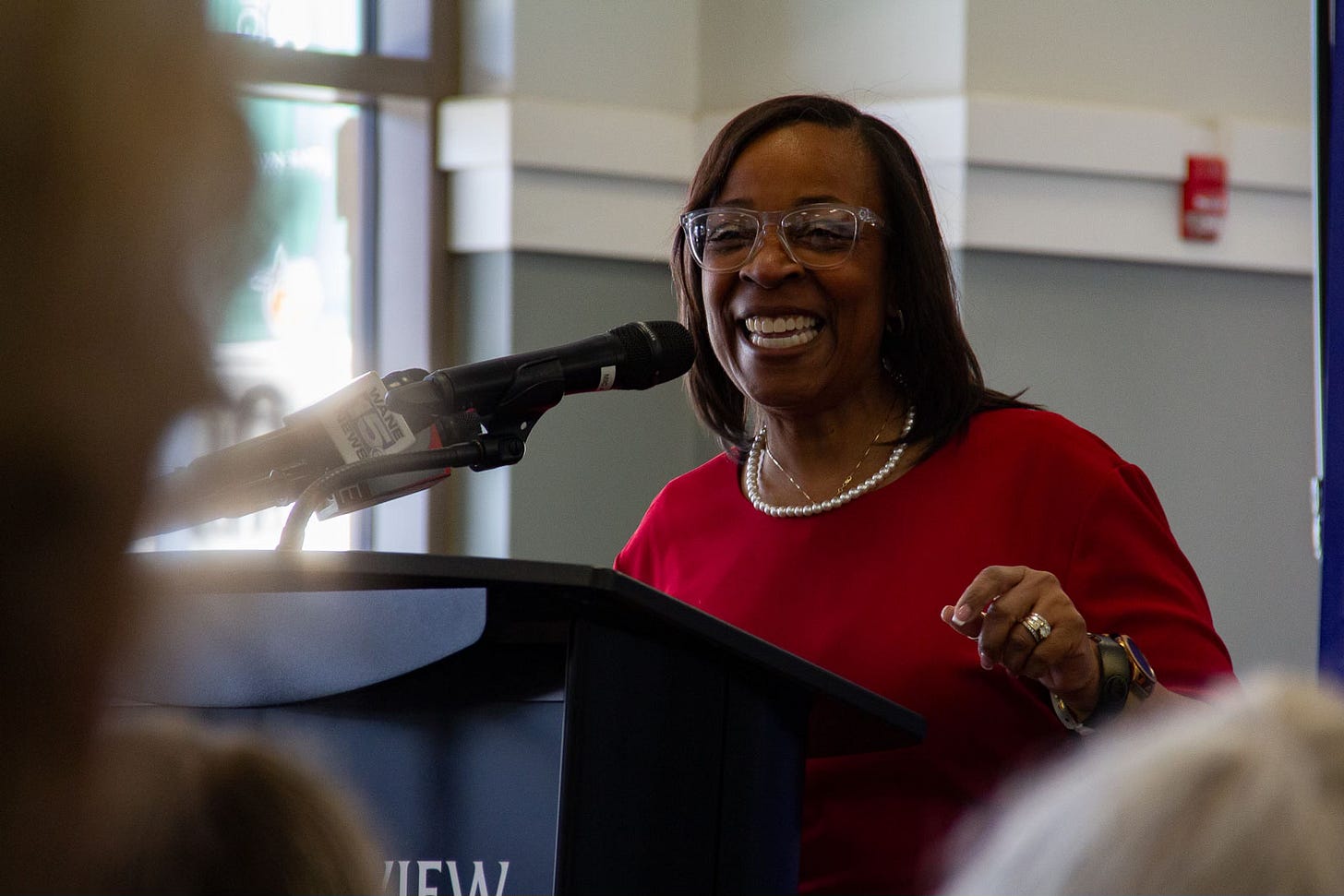

“I’m not going to read the vote totals,” he said to the crowd, which was now buzzing with anticipation, “but we do have a winner. Please welcome to the stage our new mayor: Sharon Tucker!”

He couldn’t even get out her last name before the room erupted in applause.

“That uproar, that ovation, that wasn’t just the precinct chairs,” one of them told me later. “That was the people.”

Tucker stepped up to the podium — finally center stage, directly in the spotlight — and smiled.

The precinct chairs, who had risen to their feet to give their mayor-elect a standing ovation, remained standing throughout her entire acceptance speech.

As Tucker spoke, GiaQuinta looked on, no doubt with mixed emotions. In addition to her opponent, he had been a political mentor to Tucker over the years, as he had to several of the other candidates he was standing alongside.

Fighting back tears, Tucker admitted that “in all the preparation, the one thing that I forgot to prepare [was] an acceptance speech.”

She thanked the precinct chairs for helping her make history, then asked them to join her in uniting the Democratic Party going forward.

“It’s been three long weeks. You guys have been through a lot,” she told them.

“Go home and get you some rest and look for the invite for a big party.”

Well done, sir. I've enjoyed and been appreciative of your coverage through these past few weeks. Thank you!